The feud between TikTok and UMG (what actually happened)

The real story behind the headlines 👀

*** Disclaimer

The goal of this newsletter is to help artists and musicians to better understand the basics of business so they can be better equipped to make a living doing what they love.

The best way to learn business, in my opinion, is not through definitions and graphs, but through stories and case studies. These allow the reader to see how money actually flows in the real world, rather than studying hypotheticals. It’s also much less boring…

However, please note that these newsletters are my opinions/beliefs based on my understanding of the current landscape. If you disagree with anything below, I would love to have a respectful conversation in the comments that leaves us both better informed.

Or if you want to insult me, that’s fine too I guess 🥴😵💫

“There’s no money in music” is something I hear a lot.

Our company, MAD Records, is jokingly referred to as BAM Records because we only work with “broke-ass musicians”.

But saying there’s no money in music isn’t quite accurate. In fact, it’s an outright lie.

There’s an incredible amount of money in music, it’s just rarely in the pockets of the people who make it.

Many artists refuse to involve themselves in the business-side of the music industry simply because the terms “business”, “sales”, or “marketing” feels gross and slippery…. and to be fair, they have good reason.

Watch any biopic of our favorite musical heroes and you’ll almost certainly see some brilliant creative getting manipulated by a greasy troll-man who “knows how to get things done”.

Naturally, anyone artist with a glimmer of a conscious sees the troll man and says “troll-man bad, must never become troll-man”, eschewing all business-related activities and doubling-down on the ~art~.

But funnily enough, attempting to avoid becoming the troll man by eschewing all business related aspects of music is EXACTLY what leaves you vulnerable to his tactics.

After all, if you’re not willing to run your own business… you’re gonna need some help right?

*Enter troll man*

The only way to truly vanquish the troll man is by not needing him in the first place, or, at the very least, learning enough to defend yourself against his axe-bodyspray-and-roast-beef-smelling tactics.

Does that make sense? Are you still reading?

Universal Music Group is the largest record label in the world.

In the first quarter of 2024, they grossed $2.8 b-b-b-b-billion dollars and CEO Lucian Grainge (who’s name sounds like a Batman villain) just got a compensation package approved for $150mm in cash + stock.

Now before anyone ASSUMES what my attitude is here…

I’m all for people making money.

I spent much of my life as a capitalist. I believe the consumer’s ability to choose among competitors is a brilliant tool for keeping corporations in check. I think consumers, when given real options to choose from, are traditionally pretty good at sniffing out when companies are operating in good faith.

The problem is… in whatever dystopian stage of capitalism we’re in right now, the economy is, at best, horribly incentivized, and at worst, outright corrupt.

Free-market capitalists will tell you that we are free to choose, and this competition is what keeps businesses innovating on behalf of the consumer.

But what happens when it becomes cheaper to buy your competition rather than outperform them?

(This will relate to your music career, I promise, just stick with me.)

After the Financial Crisis in 2008, the “Federal Reserve” (google them. It will be confusing to understand which is exactly the point. But in a nutshell, they run the economy) lowered interest rates to 0% to revive the economy.

This allowed businesses to take on debt extremely cheaply and reinvest in their businesses.

And it worked. Businesses (large and small) took on loads of cheap debt and started reinvesting in their businesses.

However, the Federal Reserve, for reasons best explained wearing a tinfoil hat rather than in this newsletter, let this business-loan bonanza go on a little too long, and many companies got addicted to the cheap cash. Instead of paying it off (like normal people), they’d simply re-finance the debt whenever it came due since interest rates were still effectively at 0%. Some even opted to take on MORE debt.

The products got more ridiculous. Companies burned through cash and still had investors throwing money at them. Risky projects were easy to fund, and even if they failed, companies could just take on more debt to fix it.

The party kept going and the pigs got fat and happy. It should’ve ended there.

But the Federal Reserve kept feeding the pigs by keeping interest rates at 0% for well over a decade.

Many of us sounded the alarm saying “hey, don’t those pigs look a little unwell….?”But alas, they kept shoveling cheap cash down the hungry throats of the corporate swine.

Stock prices went up or down but no one really cared because money was cheap.

If the stock went down, corporations would just take on more debt and use it to buy their own stock to raise the price (yes this is legal, google “debt-financed share buybacks”).

The analysts, traders, and investment bankers who facilitated all these transactions were told they were doing “important work” and deserved multi-million dollar salaries, when in reality, it was just scores of ex-lacrosse players huddling around a roulette table claiming they know which color is “due”.

Again, it didn’t matter if the investors made good investments, there was always more money if they needed it. Eventually, out of laziness or sheer exhaustion, the corporations ran out of ways to spend the money.

And instead of sitting back, taking a deep breath and saying “wow, that was fun huh?”…

….they started buying each other.

Kraft bought Mondelez. T-Mobile bought Sprint.

3M bought Scrub Daddy…. and Scrub Mommy went with him :(

Once corporations ran out of ways to innovate or add value with cheap debt, they decided to simply buy their competitors and cut redundant costs.

Any startup that attempted to challenge them got bought out at insane valuations, creating the generation of boat-shoe-wearing, ex-CEO’s that became “consultants” that still crawl the ClickFunnels forums today (yes I’m aware I am kind of one of them, but not really.)

And while this was good for boat-shoe sellers, it also meant that all the “disruptors” that should be putting pressure on the big corporations to innovate and improve were getting taken out.

Worse still, anyone who bothered to regulate them also got money stuffed down their throats too. Regulators got cushy jobs on corporate boards in exchange for “leniency” for their shenanigans…

And just when these pigs were splitting at the intestines, COVID hit, and the Federal Reserve responding by bringing out the firehose feeding tube, injecting trillions more dollars into the U.S. economy through cheap debt.

And in fantastically grotesque fashion, some of these overfed pigs started exploding from sheer bloat. Funny enough, whatever pigs were left starting eating their remains too.

Now at this point, you might be asking:

What about monopoly / anti-trust laws?

What about the regulators?

Why do you keep referring to pigs? What is this article even about!?

I can’t answer the last question…. but whatever anti-monopoly checks and balances existed to prevent this ghastly scene got greased over. Regulators were bought out, bribed, swindled, or simply looked the other way.

Eventually, the once diverse marketplace of the United States became just a handful of incestual moaning pigs flopping in their own shit-covered money.

But WTF does this have to do with UMG and TikTok.

And more importantly, what does this have to do with YOUR music career.

(Wouldn’t it be funny if I said nothing and I made you read that for nothing 😂)

Well, unfortunately…. Universal Music Group was one of the fat pigs left rolling around in the mud.

Don’t want to believe me? Google “UMG acquisitions” and read the headlines.

UMG owns Abbey Road Studios, Def Jam, Island Records, Republic Records, Capitol, Virgin Music Group, and many more.

UMG, like many of the major players in the music industry (LiveNation for promotion, Ticketmaster for ticketing, etc) got its slippery tentacles into the entire industry by acquiring (or simply outspending) their competition.

Even if their competitors weren’t bought outright, many partnered with UMG to leverage their vast network. And I don’t blame them, why fight the biggest name in music?

Either way, there were few labels left that were able to effectively compete with UMG and the other Goliaths.

Now you may be saying, “well, that’s capitalism baby. Survival of the fittest!” and normally I’d agree. But it’s awfully hard to disrupt a Goliath when they also have a nearly infinite supply of cheap debt at their disposal.

Even if a smaller label has a roster of incredible artists, if they’re not in that top echelon of artists (think Taylor, Justin Bieber, etc), they’re only making a fraction of what one of the major’s make.

The major’s also have clout on their side.

If your music career was exploding (hopefully it already has) and you had to choose between a $20 million deal with the label that signed Billie Eilish, or a $1 million deal with some people who walk around barefoot in Brooklyn, what would you do?

But while all these music giants were busy partying with their newfound acquisition strategy, they took their eye off the ball of one (seemingly very important) detail:

How to make money from music.

Now, on the surface they were killing it… UMG’s revenue in 2023 alone was $12 billion 🤯

But there’s a big difference in generating $12 billion in revenue, versus buying out your competitors to boost your top line.

(Put yourself in the shoes of a CEO… if you can spend a decade trying to grow your business by 50%, or you can take out a loan and double your revenue overnight by buying out a competitor… which would you do?)

But this strategy ignored a pretty fundamental trend in the music industry. The transition from physical sales to streaming left labels without a compelling value proposition.

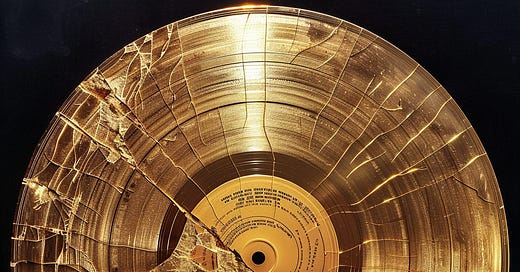

After all, the original labels were created to finance, manufacture, and distribute records. The term “record label” literally referred to the paper label on the physical record.

Streaming, in basically a single decade, made the record labels obsolete.

Online music distribution meant artists no longer needed labels to reach millions (or even billions) of listeners. And social media allowed artists to directly promote to their target audiences.

By the time the major labels returned home after their debt-infused decade of debauchery, they found themselves splitting at the seams with a portfolio of labels that basically had no real strategy for making money in the streaming era.

Well that’s awkward… isn’t it?

Are you still reading? Is this interesting? Am I crazy?

So… if independent artists.

Could distribute their music cheaply online

Promoted their music for free using social media

No longer needed to manufacture physical records

Then the question must be asked…………………………….

What the f*** do they need a record label for????

And thus we finally arrive at the TikTok / UMG feud.

For those who aren’t aware, UMG recently pulled all of their music off of TikTok, effectively muting millions of videos and stripping the platform of its most viral music (including Taylor Swift, Harry Styles, etc).

UMG cited concerns around “artist and songwriter compensation”, arguing that TikTok was benefitting from these artist catalogues without paying a fair rate for the rights to use them (TikTok accounted for ~1% of UMG’s total revenue).

And they have a point. I don’t think anyone would argue that TikTok (or any streaming platform for that matter) is paying artists fairly.

However, the question is not whether they pay fairly. We all know they don’t. The question that artists and labels alike are facing is…

Can they afford to NOT be on these platforms.

Like it or not, platforms like TikTok, Spotify, Instagram, etc are where music is consumed nowadays, and removing your music from these platforms all but guarantees that your music will NEVER be heard.

But surely, a record label the size of UMG shouldn’t need TikTok to promote its artists…. right?

Right?

After all… if their core value is no longer manufacturing or distributing records, then surely they must be able to promote their artists without relying on other tech companies, right?

Well, this is where it gets interesting (finally!)

After months of “negotiations”, UMG and TikTok struck a deal to bring their music back to the platform.

According to UMG’s statement, they were able to negotiate a

“Multi-dimensional licensing agreement that will deliver significant industry-leading benefits for UMG’s global family of artists, songwriters and labels and will return their music to TikTok’s billion-plus global community”

Sounds great right?

But the question still lingered… what were the details of this “multi-dimensional agreement” that made it any more favorable for artists?

If it was really such a big win for artists, you’d think that they’d share that information with the public as a symbol of their victory.

To find the answer to that question, we have to dig into UMG’s Q1 earnings call****.

****As a public company, UMG must disclose its earnings every quarter. Those disclosures are usually paired with an earnings call where management will discuss their performance and answer questions from Wall Street analysts. Nothing captures the spiritual beauty of music like Goldman Sachs asking questions about incremental margin growth ❤️ .

On their 2024 Q1 earnings call, analyst Adrien de Saint Hilaire from Bank of America asked this question:

“So first of all, on the TikTok deal that was announced, it might be difficult to answer. But can you say anything about how much of an upside is that deal compared to the old one financially?”

To which Executive Vice President of UMG, Michael Nash, responded:

“…with respect to your first question regarding the TikTok deal and the upside that we're expecting. We obviously can't disclose specific terms of the new deal, but we can say we've seen substantial improvement in the total value that we derive from the relationship through the combined components of what we have described as a multifaceted deal.”

Huh?

If that statement doesn’t make sense to you… you’re not alone.

In fact, that’s exactly the point.

Instead of answering the question, you’ll often hear a lot of fancy phrases that amount to no additional information than what we already knew.

And in good fashion, Goldman Sachs (defenders of the music industry), pressed for more information. Analyst Lisa Yang asked:

“…just to come back on TikTok. I know the monetization is not the main consideration, but you did say that last year, they were paying 1% of revenue that's significantly undervalued content. So could you maybe just confirm without revealing the exact number that we are above that 1%, like maybe 2% or 3% or more, but we're not still at around 1% of your overall revenue.”

To which Executive Vice President Boyd Muir responded:

…Look, we can't obviously disclose the specific terms of our deal, but we have substantially improved the total value we'll derive from this relationship. There's various components involved of what is a multifaceted deal. On compensation, specifically, revenue under this new deal marks an improvement from our last deal.

HUH?

It’s better.

How?

It just is. Stop asking.

Now…. I understand that there are aspects of their business that need to be kept private.

I also understand that these negotiations are complex and, to use their language, multifaceted.

But if they’re going to make a big show about TikTok “not compensating artists fairly”… then don’t we deserve some transparency around the new deal that proves they’re actually advocating for the artists?

After all… if record labels aren’t necessary for distribution…. or promotion…. or manufacturing….. then at the very least they should be advocates for the artist community against the tech platforms, right?

They should almost operate as a union for artists to rally behind… right?

Right?

Well… here lies the sad truth in this absurdly longwinded newsletter.

The traditional labels are no longer advocates for the artist community against the tech platforms because they are almost entirely dependent on them to survive.

According to UMG’s Q1 Earnings, “subscription and streaming” accounted for an astonishing ~73% of their Recorded Music Segment.

Now let me ask you this…

What leverage does UMG have to advocate for better rates for artists if 73% of their Recorded Music Segment revenue comes from the offending platforms?

The same is true for TikTok. One of UMG’s biggest artists (Noah Kahah) blew up almost entirely from his TikTok presence. TikTok remains the hub of pop music discovery whether UMG is on there or not.

So aside from the theatrics of pulling their music off of TikTok… what leverage does UMG have to advocate for their artists?

Suddenly the evasive and confusing answers from management around the new deal starts to make sense.

My guess is that the new deal is hardly better at all. I’m sure it’s enough to claim a victory in the media but clearly not good enough to disclose the new terms publicly.

“GOOD GOD MICHAEL, WHAT IS YOUR POINT AND HOW DOES THIS AFFECT MY MUSIC CAREER?”

*deep breath*

Here’s my point.

The labels are powerless.

Yes they have a lot of money and lawyers, which will buy them some time in the public zeitgeist. But the power and leverage in the music industry has clearly shifted, for better or for worse, from traditional labels to the streaming and social media platforms.

And while the nostalgic music fan in me is sad about that transition, it also is a massive opportunity for independent artists.

Because if the major labels need TikTok and Spotify to survive… then that means they don’t have anything that you don’t already have.

In fact, the labels are struggling to monetize their music just as much as you probably are right now.

Which means the playing fields are almost finally equal. The clever unsigned musician can build an entire career without a label, and retain the rights to their music catalogue along the way.

But the first step is admitting you don’t need a record deal.

Everything you need, you already have. Channel whatever energy you have into finding creative ways to monetize your fans instead of helplessly trying to get signed by a major label.

Throw a release party at a local cafe and livestream it on your socials.

Teach a handful of fans how to play the guitar solo on your new single.

Approach a local business and offer to license your music to them for use on their commercials, socials, etc.

Work with other artists to grow together, instead of stepping on each other for a shrinking number of useless record deals.

Whatever you do, start re-orienting your brain to focus on how you can make money on your own, rather than on getting a record deal.

If the major labels are going to monetize your music through Spotify and TikTok, you might as well do it yourself and keep the rights to your music 🤷♂️

This has been my Ted Talk.

Long Live Mad Records ⚔️🫡

- Michael

Good read, Michael. Moses Avalon has been writing(Confessions of a Music Producer) and putting on workshops for several years . He was speaking of this shift as well as the ownership of all the labels being in the hands of just a few corporations in the 2000's.

Did you see the articles about Merlin? They are f’d.